The magnificent priory kitchen was built between 1366 and 1374, its octagonal shape and rib vaulted ceiling not unlike the architecture of southern Spain.

The kitchen’s scale reflects the size of the community that would have lived here. In 1346 (20 years before the construction of the kitchen in its current form) the kitchen would have needed to feed 70 monks, 16 novices and various guests and helpers.

Presumably, roofing a kitchen with stone vaults rather than wooden beams was a precaution against fire, which would have been a high risk in a building of this scale. The height of the ceiling would have meant that the hot air would rise far above the ground, making the environment much more bearable for the kitchen staff.

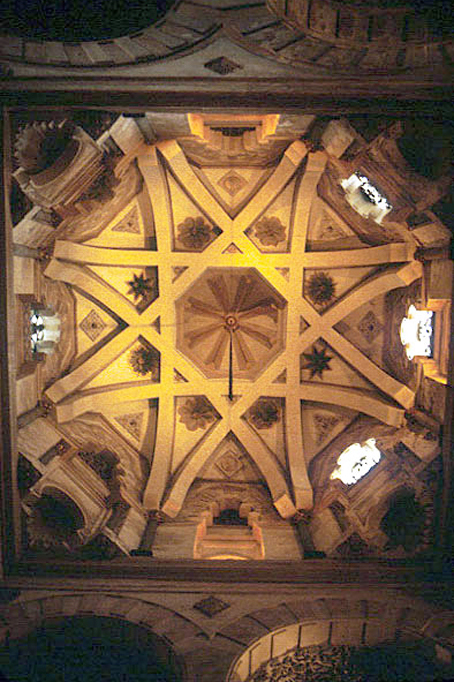

The resemblance between the roof of the great kitchen of Durham Cathedral seen here, and the construction techniques used in Cordoba, Spain, in the tenth century, to the right, is remarkable. But there are also contemporary parallels much closer to home - the kitchens of Bamburgh and Raby Castles nearby are very similar, indicating that in the fourteenth century, this was the convention for roofing the kitchens of substantial buildings in North East England.

© Michael Sadgrove

View of the vaulting in the Great Mosque of Cordoba in Spain, 10th century. These vaulting techniques, still in use almost four hundred years later, appear in buildings like the Durham Cathedral Kitchen (see top image and image to the left). This attests to their popularity and effectiveness.

A Week’s Shopping in 1346

The shopping list for Whit Week in 1346 includes “600 salt herrings; 400 white herrings; 30 salted salmon; 14 ling (a member of the cod family); 55 kelengs (?); 4 turbot; 2 horse-loads of white fish and a conger eel, plaice, sparling (young herring), and eels and fresh water fish; 9 carcasses of oxen, salted; 1 carcase and a quarter fresh; a quarter of an ox, fresh; 7 carcasses and a half of swine in salt, 6 carcasses, fresh; 14 calves, 3 kids; 26 sucking porkers; 5 stones of hog’s lard, 4 stones of cheese, butter and milk; a pottle (half a gallon) of vinegar; a pottle of honey; 14 pounds of figs and raisins, 13 pounds of almonds, 8 pounds of rice, pepper, saffron, cinnamon and other spices, and 1300 eggs. (from Durham City By Keith Proud).

It was hard to obtain fresh ingredients in medieval times, and many foodstuffs were preserved in some form or another. Meat and fish were salted, and fruits, especially those that came from afar, were dried. Seen here are raisins, figs, and cinnamon, all of which are not native to England but feature in the 14th century shopping list above.

Current Use

The Great Kitchen now forms part of Open Treasure, Durham Cathedral’s world-class visitor experience, with state-of-the-art display cases designed to showcase some of the most precious artefacts from the Cathedral’s collections.