The World Heritage List came about as the result of a general conference of the UNESCO (The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation) at its 17th session in 1972.

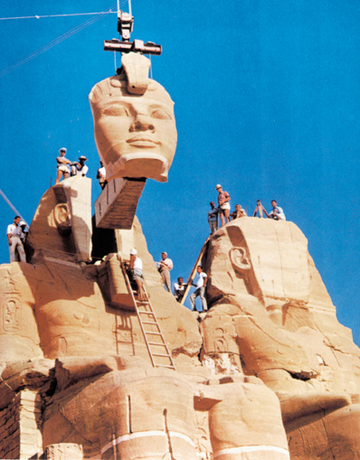

The pharonic temple of Abu Simbel in Egypt was moved in 1972 to prevent it from being submerged by the lake that was to be created by the construction of the Aswan Dam. The relocation of this massive stone temple is among UNESCO's greatest accomplishments.

© Hochtief.com

UNESCO in Action: The Florence Flood and the Aswan Dam

The early 1970s were a time when cultural and natural heritage was increasingly threatened with destruction, both by the traditional causes of decay, and by changing social and economic conditions, including urban development, population growth, and over-hunting.

UNESCO had led three significant rescue campaigns:

- Re-siting the Nubian Monuments in southern Egypt under threat of submergence by the construction of the Aswan Dam;

- Restoration of central Florence after flooding in 1966;

- Addressing the recurring problem of winter flooding in Venice;

As such, there was growing public consensus that some heritage was of outstanding importance and therefore worthy of preservation as part of the world heritage of mankind as a whole.

Principles Behind the World Heritage List

The list was based on several fundamental considerations:

- that heritage could be both cultural and natural;

- that each item of heritage was unique and irreplaceable;

- that each country in whose territory heritage lay had an obligation to safeguard it for posterity (both to its citizens and to the international community);

- that the study, knowledge and protection of heritage in various countries was conducive to mutual understanding between peoples;

- and that heritage had an important role to play in community life (social and economic), and needed to be an integral part of regional development and national planning at every level.

Aerial view of Florence during the flood of 1966. The severity of the flood was a call to action: It raised alarm bells that the world's cultural heritage was vulnerable and too precious to lose.

© Above: Bazzechi Kunsthistorisches Institut, Florence; Top Image: www.florenceflood.com

A view of Mombasa, Kenya, demonstrating what happens when the urban context of architectural heritage is not taken into account. The old-world feel of the street with its colonial buildings is ruined by the new concrete building in the centre, which is inappropriate in scale, massing and materials. Many historic cities around the world continue to be ruined by such short-sightedness.

© Francesco Siravo

Heritage in Context

The idea of preserving heritage in its environment was identified by UNESCO as being important; this was almost certainly due to a growing awareness of the wrongs of the common 19th century practise of appropriating and relocating artefacts, and of the fact that many valuable environments, both man-made and natural, were being lost.

Heritage as an Asset

UNESCO was pioneering in identifying that heritage should be seen as an asset, rather than an obstacle in the face of national development. It also recognised that countries needed to take an active role in heritage preservation, and that both public and private entities needed to get involved, making the most of advances in science and technology. Many of these are principles now taken for granted.