William as King of England

Trying to Be English

In his early days as king of England, William emphasised his role as successor to Edward the Confessor, vowing to honour the rights of all Englishman who remained loyal, and making an effort to learn Anglo-Saxon. Yet there was considerable opposition to his reign – the Normans and their cohorts, the Bretons, the Flemish and the French, being seen as foreigners. Fortunately for William, attempts to overthrow him were poorly coordinated, and he successfully overtook his opponents one by one.

Resistance and an Architectural Response

To counter pockets of resistance, William’s forces built numerous Motte and Bailey Castles. These wooden structures were easy to construct yet effective for defensive purposes. With time, stone buildings, like Durham Castle, superseded the wooden structures.

Alan Rufus, (Alan Ar Rouz) a Breton, swearing allegiance to William the Conqueror. Rufus was one of the Conqueror's key allies. It was he that led the 'Harrying of the North' - a violent attack on the North of England to suppress resistance to Norman rule. Rufus died an extremely wealthy man. By 2007 standards, he would have been worth 81 billion pounds!

© Wikipedia

Desperation and the Creation of a Franco-Norman Elite

William faced some of his most serious resistance in the north of England, where he launched harsh campaigns in 1069-1070.

This was a turning point in his relationship with England. He was crowned a second time in that year, an unprecedented event, which corresponded with the deposition of several English bishops and abbots, reflecting a growing trend to create a French Norman elite, probably in desperation at continued English resistance to his rule. It was in that year that he appointed Lanfranc, the abbot of his monastery at Caen, as archbishop of Canterbury. Lanfranc reformed the church, often moving Cathedral Sees from villages to towns. This led to a wave of cathedral construction, heralding the rise of Romanesque architecture in England.

Cold Peace and Familial Strife

In 1071, with the defeat of Hereward, the Wake of Lincolnshire, William finally put an end to major opposition of his rule.

With greater stability in place, but no real popular acceptance, William withdrew to Normandy, where political trouble brewed, most notably between William and his eldest son, Robert, leading to a battle between them in 1077-8.

The following year, seizing the opportunity of William’s political problems. Malcolm of Scotland invaded Northern England, breaking a treaty made with William in 1072.

The 1080s were a difficult decade for William. In 1083, his wife, Matilda of Flanders, instrumental in controlling Normandy in William’s absence, died. Also, in that year, William imprisoned his half brother Bishop Odo, who had served as his regent in England, for planning to travel to Rome and buy the papacy for himself. This meant that William lost the stabilising forces that enabled him to rule both sides of the channel.

The Domesday Book

A Danish invasion threatened England in 1085. William readied himself by levying taxes and putting an army together. At Christmas of that year, he gave the orders for one of the greatest administrative projects of Medieval Europe, a survey of his kingdom, which was to lead to the production of the Domesday Book. Undertaken as a means of managing taxes and the army, the census was an invaluably detailed documentation of the status quo in England. Pioneering in its scope, it was a reflection of the William’s skill as an administrator. It has been suggested that William of St Calais, the Bishop of Durham, was the driving force behind the Domesday Survey.

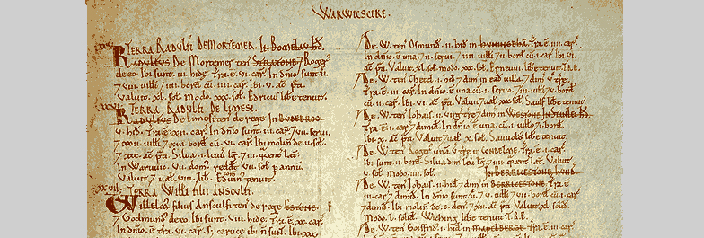

An effective administrative system is a requirement of any successful political system, and among William the Conqueror's great achievements was the Domesday Survey, which assessed the wealth of his kingdom. Seen here is a page from the Domesday Book (the result of the survey) covering the area of Warwickshire.

William’s Death

In 1087 incursions in Normandy by vassals of French king Philip, led William to launch a counter attack in early September, in which he was seriously wounded. He survived for a few days, pardoning his eldest son Robert, and confirming him as his successor as the Duke of Normandy. He also freed his brother, Bishop Odo, and named his second son, William Rufus, as the next king of England.